DPF Working Principle: Filtration and Regeneration

Understanding the DPF requires comprehension of its two core processes:

1. Filtration Process

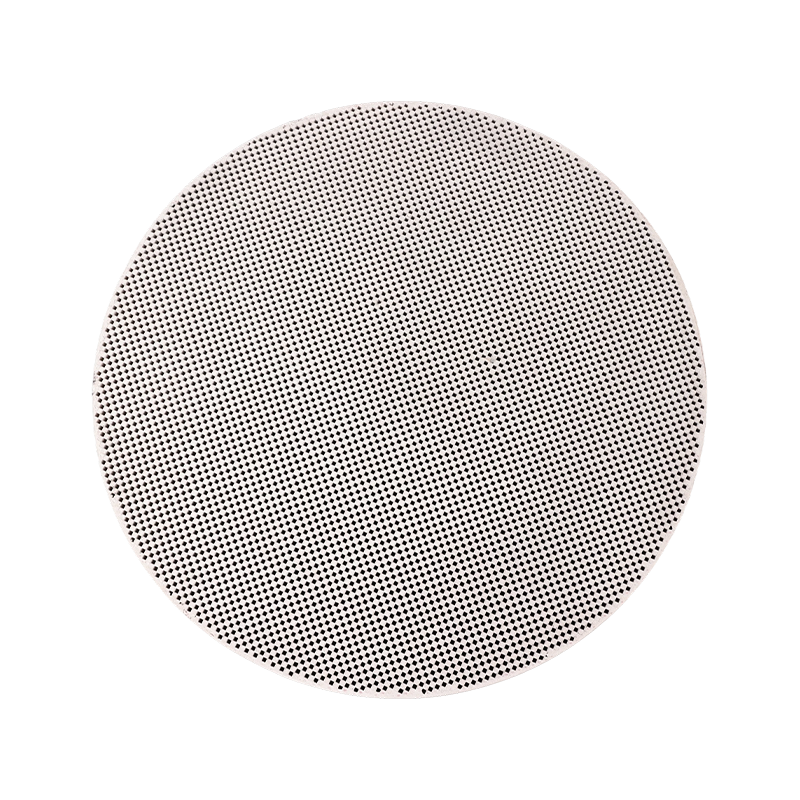

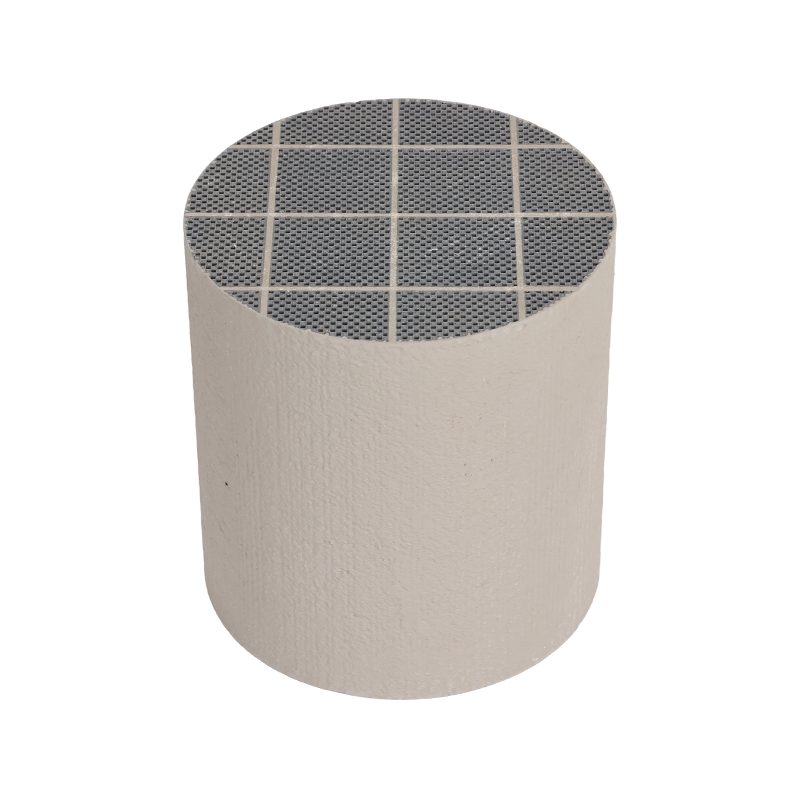

The DPF substrate is typically a honeycomb structure made of porous walls of silicon carbide or cordierite, with alternating channels blocked at the inlet and outlet ends.

Exhaust gas is forced to pass through the porous walls between channels.

Particulate matter is trapped on the walls because its size is larger than the diameter of the wall pores.

This process is highly efficient, with a soot filtration efficiency of over 95%.

2. Regeneration Process

This is the essence of DPF technology. If soot is only collected but not removed, particles will continuously accumulate, causing exhaust backpressure to rise sharply, eventually leading to engine malfunction. Therefore, the collected particulate matter must be periodically burned off, a process known as regeneration.

Core Challenge: The ignition temperature of pure soot is very high (around 550–600°C), whereas normal diesel exhaust temperatures, especially during urban driving, range only from 150–300°C and cannot naturally burn off the soot.

Role of the Catalyst: The primary purpose of the DPF catalyst is to significantly lower the oxidation temperature of soot through chemical reactions, allowing it to be burned off within the normal exhaust temperature range during engine operation.

Types and Composition of DPF Catalysts

DPF catalysts are not independent units but are integrated with the DPF substrate in the form of a coating. There are three main implementation methods:

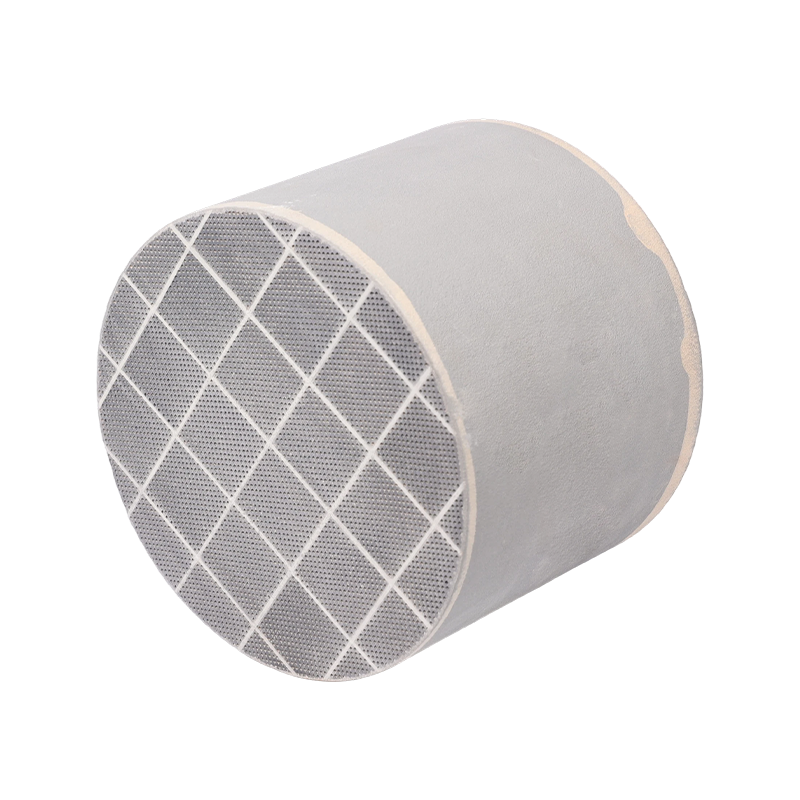

1. Catalyst-Coated DPF

This is the most common type, where the catalyst coating is directly applied onto the porous walls of the DPF substrate.

Substrate: Porous silicon carbide or cordierite DPF.

Coating: Similar to DOC, a high surface area γ-alumina is used as the base coating.

Active Components:

Precious metals such as platinum and palladium: these have been mainstream choices in early and many current systems.

Mechanism of Action:

Oxidation of NO to NO₂: The catalyst oxidizes NO in the exhaust to NO₂. NO₂ is a strong oxidizing agent that reacts with soot at relatively low temperatures (~250–300°C): C + 2NO₂ → CO₂ + 2NO. This reaction is key to achieving passive regeneration.

Direct Oxidation: At higher temperatures, the catalyst also promotes the direct reaction between oxygen and soot.

2. Fuel Additive-Type Catalyst

In this method, the catalyst is not coated on the DPF but added directly to the fuel in the form of a metal-based additive.

Additive: Typically, organometallic compounds of cerium or iron.

Principle: After combustion, metal particles from the additive enter the DPF with the exhaust gas and embed uniformly into the collected soot layer. During regeneration, these metal particles act as catalysts, significantly lowering the soot oxidation temperature (down to ~450°C).

Advantages: The catalyst mixes evenly with soot, ensuring sufficient contact and high regeneration efficiency.

Disadvantages: Requires additional additive storage and injection systems, increases costs, and metal oxide ash residues accumulate in the DPF, necessitating periodic cleaning.

3. Catalytic DPF

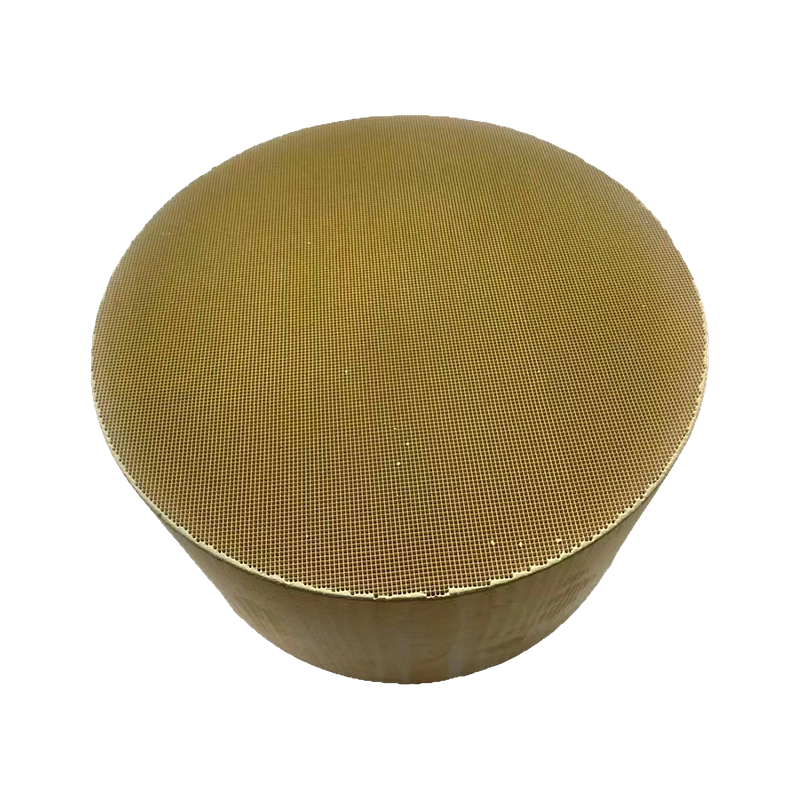

This is a concept that is easily confused but important. It refers to integrating DOC functionality and DPF functionality into a single component, i.e., applying a high-dose oxidation catalyst (such as platinum or palladium) at the inlet of the DPF.

Function: It can oxidize CO and HC like a DOC and generate NO₂ for passive regeneration, while also capturing particulate matter like a DPF.

Application: Commonly used in compact aftertreatment systems where space is limited.

DPF Regeneration Strategies

The presence of a DPF catalyst enables the following regeneration strategies:

1. Passive Regeneration

Process: During normal vehicle operation, when the exhaust temperature reaches a certain level (e.g., during highway cruising), the DPF catalyst continuously generates NO₂, which steadily oxidizes the accumulated soot.

Characteristics: This process is imperceptible to the driver and is the most desirable regeneration method. However, it requires sufficient exhaust temperature and coordination with the upstream DOC to supply NO₂.

2. Active Regeneration

Process: When the vehicle’s onboard computer detects via the differential pressure sensor that the DPF is sufficiently clogged and passive regeneration is not possible, the system intervenes actively.

Intervention Methods: By delaying fuel injection or performing post-injection, unburned fuel enters the DOC, undergoes oxidation, and produces high-temperature exhaust above 600°C, which is then directed to the DPF, allowing soot to rapidly oxidize with oxygen at high temperatures.

Role of the Catalyst: In this mode, soot can be burned off even without a catalyst at high temperatures. However, the presence of the catalyst lowers the required regeneration temperature, shortens regeneration time, and reduces fuel consumption.

3. Service Regeneration

Process: If the vehicle is consistently operated under short-distance or low-speed conditions, preventing completion of active regeneration, specialized equipment must be used by service personnel to perform forced regeneration.

Key Challenges and Considerations

1. Ash Accumulation: Additives from engine oil (such as calcium, zinc, phosphorus, sulfur, etc.) produce non-combustible ash upon combustion. The ash permanently clogs the DPF channels, causing a gradual increase in backpressure. This is the ultimate limiting factor for DPF lifespan and requires periodic disassembly, cleaning, or replacement (typically after several hundred thousand kilometers).

2. Catalyst Poisoning: Substances such as sulfur and phosphorus can poison the catalyst coating on the DPF, reducing its catalytic activity.

3. Thermal Management: Temperature control during active regeneration is critical. Excessive temperatures may cause the DPF substrate to melt or crack due to thermal stress.

4.Fuel Quality: High-sulfur fuel can severely degrade catalyst performance and generate increased sulfate ash.

English

English